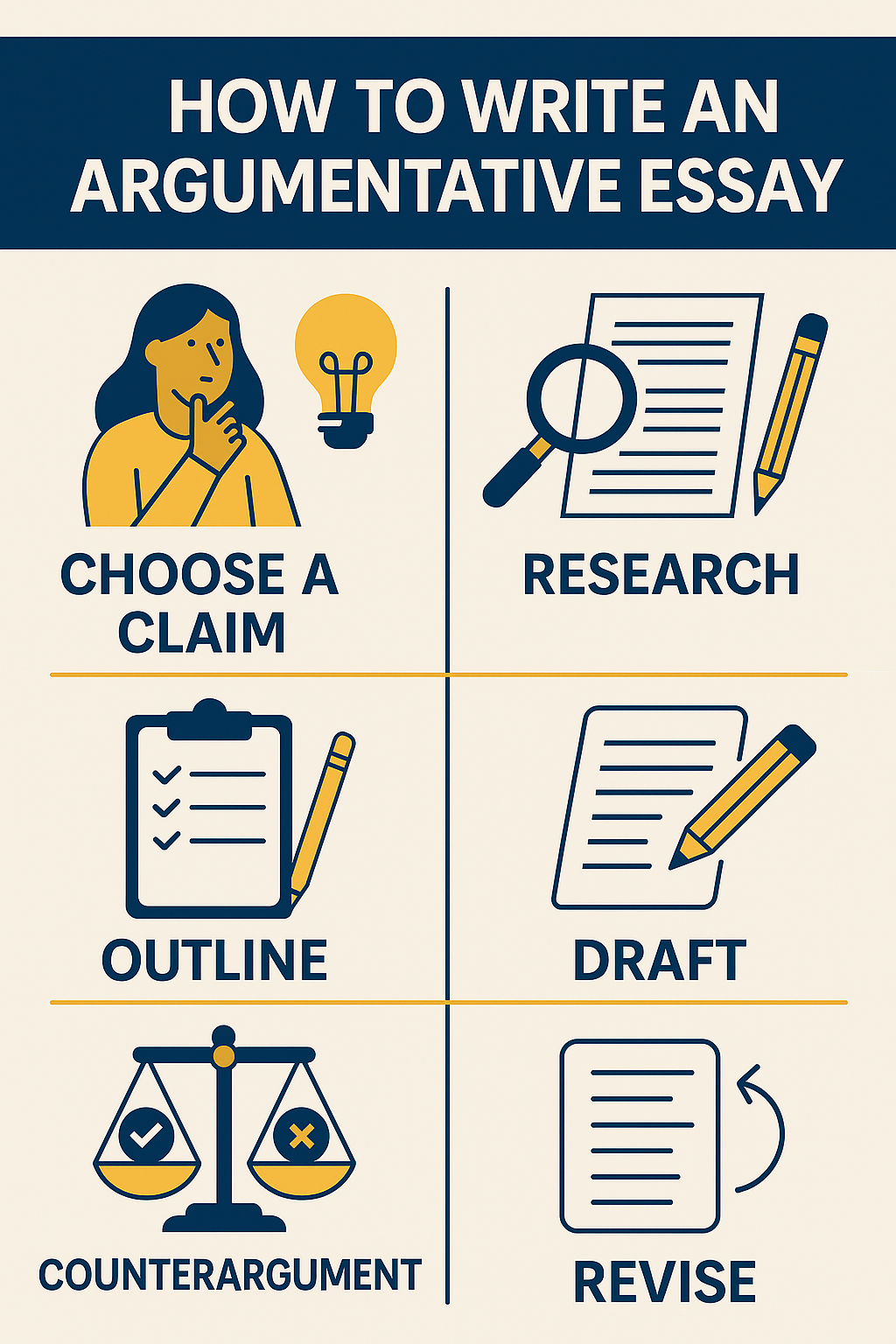

Writing well is a learnable craft. If you’re wondering how to write an argumentative essay step by step, this guide walks you through choosing a claim, structuring your ideas, handling counterarguments, and revising with confidence. By the end, you’ll have a clear process you can reuse for any topic and audience.

Understand the Purpose and What Counts as an Argument

An argumentative essay makes a defensible claim and supports it with evidence and analysis. It isn’t a rant, a summary, or a list of facts. Your goal is to persuade a reasonable reader that your position is stronger than alternatives. That means you’ll offer clear reasons, concrete evidence, and commentary that connects the dots. Think of your essay as a conversation with a skeptical but fair audience: you anticipate questions, address doubts, and show why your view is the most coherent solution to the problem at hand.

Effective arguments balance logic, credibility, and audience awareness. Logic surfaces through well-ordered reasons and sound inference; credibility grows when you use reliable sources and show your work; audience awareness means you meet readers where they are, define key terms, and avoid loaded language. Keep your scope focused. A narrow, specific claim (“School uniforms reduce socioeconomic stigma without harming student expression”) is easier to defend than a sprawling one (“All uniforms are bad”). Focus helps you select relevant evidence and avoid filler.

Choose a Debatable Claim and Research Strategically

Before you draft, anchor your process with a few high-leverage moves. The steps below keep your claim sharp, your evidence credible, and your reasoning balanced.

- Start with a focused question, then convert it into a claim you can prove. If your prompt is broad—say, social media’s impact—turn it into a precise research question: “Does TikTok improve or harm teen attention in the classroom?” After preliminary reading, refine the question into a claim with a clear stance: “TikTok short-form content reduces sustained attention during class, but structured school policies can mitigate the effect.” This move—from question to claim—gives your essay direction and an implied roadmap for evidence.

- Gather high-quality evidence and track it with simple notes. Look for data, expert viewpoints, case studies, and credible reports that speak to your claim and its strongest counterpoints. As you read, annotate with a few tags (e.g., “attention span,” “school policy,” “counterexample”) and record page numbers or timestamps so you can cite accurately later. Seek variety: statistics for scale, examples for concreteness, and expert analysis for depth. This blend strengthens your ethos and gives you flexibility when drafting.

- Guard against confirmation bias and common logical traps. Make a deliberate pass to find the best counterargument to your position. Perhaps a longitudinal study suggests the effect sizes are small, or policy compliance is inconsistent. Engaging this material early prevents straw man rebuttals and helps you adjust your claim if needed. Avoid overgeneralizations, false dilemmas, and post hoc reasoning; when you detect them in sources, use that insight: explain why an appealing but flawed claim fails, then pivot back to your evidence-based case.

Use this short checklist at the research stage and revisit it after you draft. It will help you avoid aimless summaries and build a focused, testable argument.

Craft a Focused Thesis and a Working Outline

A strong thesis is specific, arguable, and limited in scope. Aim for one or two sentences that take a clear stand and hint at your reasons. For example: “School-mandated uniforms reduce visible socioeconomic differences and improve attendance, while offering opt-in expression policies that protect student voice.” Notice the stance, the two supporting reasons, and a nod to a likely concern (expression). This sets expectations and helps you resist tangents as you draft.

Build a simple argumentative essay outline that mirrors your thesis. A reliable structure looks like this: an introduction that narrows from context to your thesis; body sections that develop distinct reasons; a fair presentation of a counterargument and your rebuttal; and a conclusion that synthesizes implications. Inside each body paragraph, use a repeatable pattern: topic sentence → evidence → analysis → link back. Topic sentences make a claim for that paragraph; evidence supports it; analysis shows how the evidence proves your point; links connect to the thesis and set up the next idea. This rhythm keeps paragraphs purposeful and prevents evidence dumps.

Plan where the counterargument belongs—and treat it with respect. You can place it after your main reasons (a common approach) or embed it within a relevant section if it directly challenges a specific claim. Either way, represent the opposing view accurately, cite its strongest evidence, and then answer it with better reasoning or superior data. This move signals intellectual honesty and strengthens your position. Readers trust writers who acknowledge complexity rather than pretending it doesn’t exist.

Draft with Clarity: Introduction, Body, Counterargument, and Conclusion

Open with context, not theatrics. A clean introduction does three jobs: frames the issue, defines essential terms, and delivers a thesis. A brief real-world snapshot or a statistic can help, but resist long anecdotes. Keep the path visible: “Here’s the problem, here’s why it matters, and here’s my position.” Put your thesis at or near the end of the introduction so readers know where the essay is headed.

Develop each body paragraph around one claim and make the analysis do the heavy lifting. Lead with a topic sentence that clearly advances one reason from your outline. Then bring in your evidence: a study result, an expert explanation, or a concrete example. Follow with analysis that explains the significance of that evidence—how it works, why it matters, and what it implies for your overall case. Aim for a healthy ratio where analysis is at least as long as the quoted or paraphrased material. Use transitions (“Consequently,” “By contrast,” “More importantly”) to show logical relationships and keep momentum.

Present the counterargument fairly, then rebut it with precision. Choose the strongest objection a reasonable critic would raise—cost, feasibility, unintended consequences—and articulate it as that critic would. Cite an example or a data point that gives it weight. Then respond: expose a flawed assumption, supply overlooked evidence, or concede a valid point while reframing its importance. For instance, you might concede that uniform programs have start-up costs, but show that long-term savings from simplified dress codes and reduced disciplinary actions offset those costs. End the paragraph by reconnecting to your thesis.

Conclude your case by synthesizing—not repeating. Rather than rehashing points, explain what follows if your claim stands: policy implications, practical next steps, or areas that deserve further study. Avoid introducing new evidence. Instead, highlight the throughline from your thesis to your most convincing reasons and the way your rebuttal resolves a key tension. A strong last sentence looks forward: it suggests a decision, a guideline, or a principle readers can carry into similar debates.

Revise, Edit, and Proof for Credibility

Revision is where an adequate draft becomes a persuasive essay. Start with “macro” questions: Does every section serve the thesis? Do paragraphs appear in the best order? Does each topic sentence make a defensible claim? Try a quick reverse outline—write a one-line summary next to each paragraph. If any line doesn’t clearly advance your argument, cut or reshape that paragraph. Look for balance: if one reason dwarfs the others, either trim it or fold minor reasons into it so your structure matches your thesis.

Polish the voice, tighten the prose, and check for logic. Replace vague verbs (“is,” “has,” “does”) with precise actions where possible. Trim filler phrases (“in order to,” “it is important to note that”) and keep sentences under about 25 words on average. Scan for logical fallacies and hedging that undercuts your confidence. When quoting, keep excerpts short and integrate them grammatically; paraphrase when the wording isn’t crucial and cite the idea cleanly. Consistency matters too—use one style for headings, one tense for your analysis, and one citation system across the paper.

Use a short revision checklist before you submit.

- Thesis is specific, arguable, and proportionate to the essay’s scope.

- Each body paragraph follows topic sentence → evidence → analysis → link.

- Counterargument is stated fairly and answered with stronger evidence or reasoning.

- Transitions clarify relationships (cause, contrast, concession, result).

- Sentences are concise; passive voice appears only when it helps clarity.

- Formatting and citations are consistent; mechanics (spelling, punctuation) are clean.